The Simplex Process

A Robust Creative Problem-Solving Process

Work through the cycle.

© iStockphoto/centyr

When you're solving business problems, it's all-too-easy easy to skip over important steps in the problem-solving process, meaning that you can miss good solutions, or, worse still, fail to identify the problem correctly in the first place.

One way to prevent this happening is by using the Simplex Process. This powerful step-by-step tool helps you identify and solve problems creatively and effectively. It guides you through each stage of the problem-solving process, from finding the problem to implementing a solution. This helps you ensure that your solutions are creative, robust and well considered.

In this article, we'll look at each step of the Simplex Process. We'll also review some of the tools and resources that will help at each stage.

About the Tool

The Simplex Process was created by Min Basadur, and was popularized in his book, "The Power of Innovation."

It is suitable for problems and projects of any scale. It uses the eight stages shown in Figure 1, below:

Rather than seeing problem-solving as a single straight-line process, Simplex is represented as a continuous cycle.

This means that problem-solving should not stop once a solution has been implemented. Rather, completion and implementation of one cycle of improvement should lead straight into the next.

We'll now look at each step in more detail.

1. Problem Finding

Often, finding the right problem to solve is the most difficult part of the creative process.

So, the first step in using Simplex is to start doing this. When problems exist, you have opportunities for change and improvement. This makes problem finding a valuable skill!

Problems may be obvious. If they're not, they can often be identified using trigger questions like the ones below:

•What would our customers want us to improve? What are they complaining about?

•What could they be doing better if we could help them?

•Who else could we help by using our core competences?

•What small problems do we have which could grow into bigger ones? And where could failures arise in our business process?

•What slows our work or makes it more difficult? What do we often fail to achieve? Where do we have bottlenecks?

•How can we improve quality?

•What are our competitors doing that we could do?

•What is frustrating and irritating to our team?

These questions deal with problems that exist now. It's also useful to try to look into the future. Think about how you expect markets and customers to change over the next few years; the problems you may experience as your organization expands; and social, political and legal changes that may affect it. (Tools such as PEST Analysis will help you to do this.)

It's also worth exploring possible problems from the perspective of the different "actors" in the situation – this is where techniques such as CATWOE can be useful.

At this stage you may not have enough information to define your problem precisely. Don't worry about this until you reach step 3!

2. Fact-Finding

The next stage is to research the problem as fully as possible. This is where you:

•Understand fully how different people perceive the situation.

•Analyze data to see if the problem really exists.

•Explore the best ideas that your competitors have had.

•Understand customers' needs in more detail.

•Know what has already been tried.

•Understand fully any processes, components, services, or technologies that you may want to use.

•Ensure that the benefits of solving the problem will be worth the effort that you'll put into solving it.

With effective fact-finding, you can confirm your view of the situation, and ensure that all future problem-solving is based on an accurate view of reality.

3. Problem Definition

By the time you reach this stage, you should know roughly what the problem is, and you should have a good understanding of the facts relating to it.

From here you need to identify the exact problem or problems that you want to solve.

It's important to solve a problem at the right level. If you ask questions that are too broad, then you'll never have enough resources to answer them effectively. If you ask questions that are too narrow, you may end up fixing the symptoms of a problem, rather than the problem itself.

Min Basadur, who created the Simplex process, suggests saying "Why?" to broaden a question, and "What's stopping you?" to narrow a question.

For example, if your problem is one of trees dying, ask "Why do I want to keep trees healthy?" This might broaden the question to "How can I maintain the quality of our environment?"

A "What's stopping you?" question here could give the answer "I don't know how to control the disease that is killing the tree."

Big problems are normally made up of many smaller ones. This is the stage at which you can use a technique like Drill Down to break the problem down to its component parts. You can also use the 5 Whys Technique, Cause and Effect Analysis and Root Cause Analysis to help get to the root of a problem.

Tip:

A common difficulty during this stage is negative thinking – you or your team might start using phrases such as "We can't..." or "We don't," or "This costs too much." To overcome this, address objections with the phrase "How might we...?" This shifts the focus to creating a solution.

4. Idea Finding

The next stage is to generate as many problem-solving ideas as possible.

Ways of doing this range from asking other people for their opinions, through programmed creativity tools and lateral thinking techniques, to Brainstorming. You should also try to look at the problem from other perspectives. A technique like The Reframing Matrix can help with this.

Don't evaluate or criticize ideas during this stage. Instead, just concentrate on generating ideas. Remember, impractical ideas can often trigger good ones! You can also use the Random Input technique to help you think of some new ideas.

5. Selection and Evaluation

Once you have a number of possible solutions to your problem, it's time to select the best one.

The best solution may be obvious. If it's not, then it's important to think through the criteria that you'll use to select the best idea. Our Decision Making Techniques section lays out a number of good methods for this. Particularly useful techniques include Decision Tree Analysis, Paired Comparison Analysis, and Grid Analysis.

Once you've selected an idea, develop it as far as possible. It's then essential to evaluate it to see if it's good enough to be considered worth using. Here, it's important not to let your ego get in the way of your common sense.

If your idea doesn't offer a big enough benefit, then either see if you can generate more ideas, or restart the whole process. (You can waste years of your life developing creative ideas that no-one wants!)

Techniques to help you to do this include:

•Risk Analysis, which helps you explore where things could go wrong.

•Impact Analysis, which gives you a framework for exploring the full consequences of your decision.

•Force Field Analysis, which helps you explore the pressures for and against change.

•Six Thinking Hats, which helps you explore your decision using a range of valid decision-making styles.

•Use of NPVs and IRRs, which help you ensure that your project is worth running from a financial perspective.

6. Planning

Once you've selected an idea, and are confident that your idea is worthwhile, then it's time to plan its implementation.

Action Plans help you manage simple projects – these lay out the who, what, when, where, why and how of delivering the work.

For larger projects, it's worth using formal project management techniques. By using these, you'll be able to deliver your implementation project efficiently, successfully, and within a sensible time frame.

Where your implementation has an impact on several people or groups of people, it's also worth thinking about change management. Having an appreciation of this will help you assure that people support your project, rather than opposing it or cancelling it.

7. Sell Idea

Up to this stage you may have done all this work on your own or with a small team. Now you'll have to sell the idea to the people who must support it. These may include your boss, investors, or other stakeholders involved with the project.

In selling the project you'll have to address not only its practicalities, but also things such internal politics, hidden fear of change, and so on.

Tip:

You can learn more about how to get support for your ideas with our Bite-Sized Training Session, Sell Your Idea.

8. Action

Finally, after all the creativity and preparation comes action!

This is where all the careful work and planning pays off. Again, if you're implementing a large-scale change or project, you might want to brush up on your change management skills to help ensure that the process is implemented smoothly.

Once the action is firmly under way, return to stage 1, Problem Finding, to continue improving your idea. You can also use the principles of Kaizen to work on continuous improvement.

Key Points:

Simplex is a powerful approach to creative problem-solving. It is suitable for projects and organizations of almost any scale.

The process follows an eight-stage cycle. Upon completion of the eight stages you start it again to find and solve another problem. This helps to ensure continuous improvement.

Stages in the process are:

•Problem finding.

•Fact finding.

•Problem Definition.

•Idea Finding.

•Selection and Evaluation.

•Planning.

•Selling of the Idea.

•Action.

By moving through these stages you ensure that you solve the most significant problems with the best solutions available to you. As such, this process can help you to be intensely creative

Pesquisar neste blogue

sexta-feira, 28 de janeiro de 2011

terça-feira, 25 de janeiro de 2011

Exercícios de memória em idosos

Exercícios mentais para idosos melhoram memória, velocidade de processar informações e de raciocinar em atividades do dia-a-dia

De acordo com estudo, assim como a atividade física traz benefícios para o corpo, exercícios mentais podem ajudar a manter a mente de idosos funcionando melhor, com resultados duradouros.

Idosos que receberam apenas 10 sessões de treinamento mental apresentaram melhoras na memória, no raciocínio e na velocidade de processar informações cinco anos após as sessões, dizem os pesquisadores que conduziram o Advanced Cognitive Training for Independent and Vital Elderly study, ou ACTIVE. Os resultados foram publicados na edição de 20 de dezembro do Journal of the American Medical Association.

Os exercícios mentais foram projetados para melhorar as habilidades de raciocínio de idosos e determinar se estas melhorias poderiam também afetar sua capacidade de seguir corretamente instruções de utilização de medicamentos ou reagir rapidamente aos sinais de tráfego.

"Nossos achados sugerem claramente que pessoas que adotam um programa ativo de treinamento mental na terceira idade podem obter benefícios duradouros desse treinamento," disse o pesquisador Michael Marsiske, professor da University of Florida College of Public Health and Health Professions. "Os resultados positivos do ACTIVE sugerem fortemente que muitos adultos possam aprender e se desenvolver mesmo em idade mais avançada."

Os investigadores descobriram também evidências de "transferência" do treinamento às funções diárias. Comparados àqueles que não receberam treinamento mental, participantes de três grupos de treinamento - memória, velocidade de processar e de raciocinar - relataram menos dificuldade em executar tarefas como cozinhar, usar a medicação e controlar finanças.

"Nós possuíamos aproximadamente 25 anos de conhecimento, antes deste estudo, que sugeria que as habilidades de raciocínio de idosos poderiam ser treinadas, mas nós não sabíamos se estes ganhos mentais afetariam habilidades na prática diária" disse Marsiske. "Neste estudo nós obtivemos evidências de que treinar as funções mentais básicas pode também melhorar a habilidade dos idosos em executar tarefas de sua rotina."

Realizado entre 1998 e 2004, o estudo ACTIVE é o primeiro realizado em grande escala alternando treinamento cognitivo em idosos saudáveis. Financiado pelo National Institute on Aging e pelo National Institute of Nursing Research, o estudo envolveu 2.802 idosos de 65 a 96 anos, os quais foram divididos em grupos para receber o treinamento em memória, raciocínio ou velocidade de processar, em 10 sessões de 90 minutos cada, durante seis semanas. O grupo de controle não recebeu treinamento.

Os idosos do grupo de treinamento da memória aprenderam estratégias para recordar listas de palavra e seqüências de itens, material textual e idéias principais e detalhes de histórias. Os participantes do grupo de raciocínio receberam instrução em como resolver problemas que seguem padrões, uma habilidade útil em tarefas como ler uma programação de horário de ônibus ou preencher um formulário. O treinamento de velocidade de processamento foi feito com programas para computadores que focalizaram a habilidade para identificar rapidamente e encontrar informações visuais, habilidades usadas ao procurar números na lista de telefone ou ao reagir aos sinais de tráfego.

Quando imediatamente testados depois do período de treinamento, 87% dos participantes do treinamento de velocidade, 74% do de raciocínio e 26% do de memória mostraram melhoria na confiança em suas respectivas habilidades mentais.

Em relatórios posteriores, os investigadores encontraram que as melhorias persistiram por dois anos após o treinamento, particularmente para os idosos que foram sorteados para receber treinamento de reforço de um a três anos após o treinamento original.

Fonte: http://www.news.med.br/p/exercicios+mentais+para+idosos+melh-10444.html

De acordo com estudo, assim como a atividade física traz benefícios para o corpo, exercícios mentais podem ajudar a manter a mente de idosos funcionando melhor, com resultados duradouros.

Idosos que receberam apenas 10 sessões de treinamento mental apresentaram melhoras na memória, no raciocínio e na velocidade de processar informações cinco anos após as sessões, dizem os pesquisadores que conduziram o Advanced Cognitive Training for Independent and Vital Elderly study, ou ACTIVE. Os resultados foram publicados na edição de 20 de dezembro do Journal of the American Medical Association.

Os exercícios mentais foram projetados para melhorar as habilidades de raciocínio de idosos e determinar se estas melhorias poderiam também afetar sua capacidade de seguir corretamente instruções de utilização de medicamentos ou reagir rapidamente aos sinais de tráfego.

"Nossos achados sugerem claramente que pessoas que adotam um programa ativo de treinamento mental na terceira idade podem obter benefícios duradouros desse treinamento," disse o pesquisador Michael Marsiske, professor da University of Florida College of Public Health and Health Professions. "Os resultados positivos do ACTIVE sugerem fortemente que muitos adultos possam aprender e se desenvolver mesmo em idade mais avançada."

Os investigadores descobriram também evidências de "transferência" do treinamento às funções diárias. Comparados àqueles que não receberam treinamento mental, participantes de três grupos de treinamento - memória, velocidade de processar e de raciocinar - relataram menos dificuldade em executar tarefas como cozinhar, usar a medicação e controlar finanças.

"Nós possuíamos aproximadamente 25 anos de conhecimento, antes deste estudo, que sugeria que as habilidades de raciocínio de idosos poderiam ser treinadas, mas nós não sabíamos se estes ganhos mentais afetariam habilidades na prática diária" disse Marsiske. "Neste estudo nós obtivemos evidências de que treinar as funções mentais básicas pode também melhorar a habilidade dos idosos em executar tarefas de sua rotina."

Realizado entre 1998 e 2004, o estudo ACTIVE é o primeiro realizado em grande escala alternando treinamento cognitivo em idosos saudáveis. Financiado pelo National Institute on Aging e pelo National Institute of Nursing Research, o estudo envolveu 2.802 idosos de 65 a 96 anos, os quais foram divididos em grupos para receber o treinamento em memória, raciocínio ou velocidade de processar, em 10 sessões de 90 minutos cada, durante seis semanas. O grupo de controle não recebeu treinamento.

Os idosos do grupo de treinamento da memória aprenderam estratégias para recordar listas de palavra e seqüências de itens, material textual e idéias principais e detalhes de histórias. Os participantes do grupo de raciocínio receberam instrução em como resolver problemas que seguem padrões, uma habilidade útil em tarefas como ler uma programação de horário de ônibus ou preencher um formulário. O treinamento de velocidade de processamento foi feito com programas para computadores que focalizaram a habilidade para identificar rapidamente e encontrar informações visuais, habilidades usadas ao procurar números na lista de telefone ou ao reagir aos sinais de tráfego.

Quando imediatamente testados depois do período de treinamento, 87% dos participantes do treinamento de velocidade, 74% do de raciocínio e 26% do de memória mostraram melhoria na confiança em suas respectivas habilidades mentais.

Em relatórios posteriores, os investigadores encontraram que as melhorias persistiram por dois anos após o treinamento, particularmente para os idosos que foram sorteados para receber treinamento de reforço de um a três anos após o treinamento original.

Fonte: http://www.news.med.br/p/exercicios+mentais+para+idosos+melh-10444.html

quinta-feira, 20 de janeiro de 2011

Doença de Alzheimer e Fisioterapia

A doença de Alzheimer é uma doença neuropsiquiátrica progressiva do envelhecimento encontradas em adultos de meia-idade e, particularmente, em mais velhos, que afeta a substância cerebral e é caracterizada pela perda inexorável da função cognitiva, bem como distúrbios afetivos e comportamentais. A principal causa de demência em adultos com mais de 60 anos, o mal de Alzheimer, é responsável por alterações de comportamento, de memória e de pensamento (1).

A doença se caracteriza pela morte gradual de neurônios, as células nervosas do cérebro. As causas desse desastre são pouco conhecidas. Sabe-se que ele está relacionada a um acúmulo de duas proteínas, a beta-amilóide (2).

Doença de Alzheimer

A doença de Alzheimer caracteriza-se pela atrofia do córtex cerebral. O processo geralmente é difuso, mas pode ser mais grave nos lobos frontal, parietal e temporal. O grau de atrofia varia(3).

O envelhecimento normal do cérebro também se acompanha de atrofia, há uma superposição no grau de atrofia do cérebro de pacientes idosos com Alzheimer e pessoas da mesma idade afetadas pela doença. Ao exame microscópio, há perda tanto de neurônio como de neurópilo no córtex e, ocasionalmente, se observa uma desmielinização secundária na substância branca subcortical. Com o uso da morfometria quantitativa, a maior perda é a de grandes neurônios corticais (4).

Os achados mais característicos são placas senis e emaranhadas neurofibrilares argentofílicos. A placa senil é encontrada em todo o córtex e hipocampo e o número de placas por campo microscópio correlaciona-se com o grau de perda intelectual. Emaranhados neurofibrilares são estruturas fibrilares intracitoplasmáticas neuronais (5).

A degeneração e a perda neuronal são gerais, embora especialmente acentuadas nas células piramidais do hipocampo e células piramidais grandes no córtex associativo. A degeneração aparece cedo no núcleo basal de Meynert e mais tarde nos lócus coeruleos. A patologia inclui a presença de desarranjos neurofibrilares, placas neuríticas e degeneração granulovacuolar. Os desarranjos são massas intraneurofibrilares de filamentos citoplásticos (4).

Epidemiologia

Nos EUA, a prevalência da doença de Alzheimer em pessoas de 65 anos de idade ou mais é estimada como sendo de 10,3 %, elevando-se para 47 % naquelas acima de 80 anos. Até 2,6 % das pessoas acima dos 65 anos vem apresentar a Doença de Alzheimer anualmente. A freqüência varia pouco por sexo ou grupo étnico(1).

Etiologia

Embora a causa da Doença de Alzheimer não tenha sido estabelecida, há fortes suspeitas de uma base genética. A concordância para Doença de Alzheimer em gêmeos homozigóticos é maior que em gêmeos dizigóticos (3).

Agentes infecciosos e contaminantes ambientais, incluindo vírus lentos e metais (por exemplo o alumínio) são fatores etiológicos suspeitos. Os papéis destes fatores ainda não foram comprovados; no entanto, estes fatores ambientais estão sendo submetidos à investigação ativa. O envelhecimento normal está associado com decréscimo de alguns neurotransmissores, bem como com alguns dos achados neuropatológicos da doença. Portanto, surgiu a questão sobre se a doença seria devido a uma aceleração das alterações normais do envelhecimento (3).

As lesões crânio encefálicas, baixos níveis de instrução e síndrome de Down em um parente em primeiro grau também se associa a maior risco de doença de Alzheimer (3).

O quadro clínico da doença de Alzheimer caracteriza-se por um declínio insidioso, progressivo da memória e de outras funções corticais como linguagem, conceito, julgamento, habilidades visuo-espaciais. Progressivamente instalam-se alterações intelectuais e de esfera afetiva, mas sobressaem os distúrbios de funções simbólicas: apraxias, agnosias (perda da capacidade de interpretar o que vê, ouve ou sente) e afasias. Pode ocorrer manifestação psicótica, como delírios e crises convulsivas (6). Apresentam geralmente delírios de infidelidade conjugal e roubos. Esses pacientes podem vagar, marchar, abrir e fechar gavetas rapidamente, bem como fazer as mesmas perguntas várias vezes. Anormalidades do ciclo sono-vigília podem tornar-se evidentes, como ficar acordado durante a noite, por pensar que ainda é dia claro (3). Alguns pacientes desenvolvem uma marcha arrastada, com rigidez muscular generalizada associada à lentidão e inadequação do movimento. Possuem com frequência um aspecto parkinsoniano, mas raramente tem tremor em repouso rápido e rítmico. Podem evidenciar reflexos tendíneos hiperativos e reflexos de sucção e muxoxo. Abalos mioclônicos (contrações bruscas breves de vários músculos ou de todo o corpo) podem ocorrer espontaneamente ou em respostas a estímulos físicos ou auditivos (2).

As perdas cognitivas aumentam e o indivíduo evolui até ficar totalmente dependente de outros para a execução de suas atividades mais básicas. Em estágios mais avançados passa a não se alimentar, engasgar-se com a comida e saliva, o vocabulário fica restrito a poucas palavras, perde a capacidade de sorrir, sustentar a cabeça, fica acamado e a morte sobrevém em conseqüência de complicações como pneumonia, desidratação ou sepsis (6).

A demência senil do tipo Alzheimer pode ainda ser subdividida de acordo com o estágio clínico, mas existe grande variabilidade e a evolução dos estágios freqüentemente não é tão ordenada como se poderia deduzir da descrição que vem

Estágio Inicial: perda da memória recente, incapacidade de aprender e reter informações novas, problemas de linguagem, labilidade de humor e, possivelmente, alterações de personalidade. Os pacientes podem apresentar dificuldade progressiva para desempenhar as atividades de vida diária. Irritabilidade, hostilidade e agitação podem ocorrer como resposta à perda de controle e de memória. O estágio inicial, no entanto, pode não comprometer a sociabilidade (7).

Estágio Intermediário: completamente incapaz de aprender e lembrar de informações novas. Os pacientes se perdem constantemente, frequentemente a ponto de conseguirem encontrar o seu próprio quarto ou banheiro. Embora continuem a deambular, estão em risco significativo de quedas ou acidentes secundários à confusão. O paciente pode precisar de assistência nas AVDs. A desorganização comportamental ocorre na forma de perambulação, agitação, hostilidade, falta de cooperação ou agressividade física. Neste estágio, o paciente já perdeu todo o senso de tempo e lugar (7).

Estágio grave ou terminal: incapaz de andar, totalmente incontinente e incapaz de desempenhar qualquer AVD. Podem ser incapazes de deglutir e podem necessitar de alimentação por sonda nasogastrica. Estão em risco de pneumonia, desnutrição e necrose da pele por pressão (7).

A evolução da doença é gradual, e não rápida ou fulminante; existe um declínio constante, embora os sintomas em alguns pacientes pareçam se estabilizar durante algum tempo. Não ocorrem sinais motores ou outros sinais neurológicos focais ate tardiamente na doença (1). A duração típica da doença é de 8 a 10 anos, mas a evolução varia de 1 a 25 anos. Por motivos desconhecidos, alguns pacientes com Alzheimer evidenciam um declínio gradual e lento da função, enquanto outros têm platôs prolongados sem deterioração importante (2). O estágio final da doença de Alzheimer é coma e morte. (1)

Dentre as principais características estão (7):

Perda de memória: pode ter conseqüência na vida diária, de muitas maneiras, conduzindo a problemas de comunicação, riscos de segurança e problemas de comportamento.

Memória episódica: é a memória que as pessoas têm de episódios da sua vida, passando do mais mundano ao mais pessoalmente significativo.

Memória semântica: esta categoria abrange a memória do significado das palavras, como por exemplo, uma flor ou um cão.

Memória de procedimento: esta é a memória de como conduzir os nossos atos quer física como mentalmente, por exemplo, como usar uma faca e um garfo, ou jogar xadrez.

Apraxia: é o termo usado para descreve a incapacidade para efetuar movimentos voluntários e propositados, apesar do fato da força muscular, da sensibilidade e da coordenação estarem intactas.

Afasia: é o termo utilizado para descrever a dificuldade ou perda de capacidade para falar, ou compreender a linguagem falada, escrita ou gestual, em resultado de uma lesão do respectivo centro nervoso.

Agnosia: é o termo utilizado para descrever a perda de capacidade para reconhecer o que são os objetos, e para que servem.

Comunicação: As pessoas com doença de Alzheimer tem dificuldades na emissão e na compreensão da linguagem, o que, por sua vez, leva a outros problemas.

Mudança de personalidade: uma pessoa que tenha sido sempre calma, educada e afável pode comportar-se de uma forma agressiva e doentia. São comuns as mudanças bruscas e freqüentes de humor.

Mudanças físicas: a perda de peso pode ocorrer, redução de massa muscular, escaras de decúbito, infecções, pneumonia.

A evolução é progressiva, inevitavelmente em incapacidade completa e morte. Ás vezes há estabilizações, durante as quais o distúrbio cognitivo permanece inalterado por um ou dois anos, mas depois a progressão é retomada. A duração é geralmente entre 4 a 10 anos, com extremos de menos de 1 ano e a mais de 20 anos (8).

Tratamento

Por enquanto, não existe tratamento preventivo ou curativo para a doença de Alzheimer. Existe uma série de medicamentos que ajudam a aliviar alguns sintomas, tais como agitação, ansiedade, depressão, confusão e insônia. Infelizmente, estes medicamentos são apenas eficazes para um número limitado de doentes, apenas por um breve período de tempo e podem causar efeitos secundários indesejados. Por isso, aconselha-se geralmente a evitar a medicação, a menos que seja realmente necessária (7).

Descobriu-se que os doentes que têm a doença de Alzheimer têm níveis reduzidos de acetilcolina, um neurotransmissor (substância química responsável pela transmissão de mensagens de uma célula para outra) que intervém nos processos da memória (9).

Foram introduzidos, em alguns países, determinados medicamentos que inibem a enzima responsável pela destruição da acetilcolina. (4).

Os resultados no tratamento da doença são difíceis e frustrantes, pois não há medidas específicas e a ênfase primária é o alívio em longo prazo dos problemas comportamentais e neurológicos associados (2).

O tratamento é multimodal, desenvolvido e modificado com a progressão da doença, podendo ser obtido através da intervenção farmacológica (visando à fisiopatologia e sintomas da doença como ilusões e distúrbios do sono) e da intervenção comportamentais (melhora sintomas específicos bem como as AVDs). Atualmente os agentes farmacológicos empregados no tratamento visam inibir a acetilcolinesterase para aumentar os níveis de acetilcolina diminuídos no cérebro dos pacientes com Alzheimer. Os inibidores utilizados atualmente (utilizados apenas em doenças com déficit colinérgico como Alzheimer) são: Tacrina (melhora apatia e ansiedade), Donepezil (1).

Fisioterapia

Designa a habilitar o indivíduo comprometido funcionalmente, a novamente desempenhar suas AVDs, da melhor maneira e pelo menor tempo possível, com mais autonomia. Os principais aspectos da assistência são preventivos, elaborados para manter o indivíduo mais ativo e independente possível. No maior grau que for possível, a atividade deve ser encorajada para manter a força, ADM e estado de alerta (9).

Promover somente a ajuda que é absolutamente necessária, com os pacientes continuando a realizar sozinhos máximo de AVDs possível; o paciente precisa ser capaz de lembrar o comando, identificar o objeto (exemplo, escova de dente), e realizar a ação motora (8).

O processo de reabilitação também inclui a realização de modificações ambientais necessárias para segurança do paciente e de modo que esse possa viver em um ambiente o mais aberto possível (8). Quedas podem ser devido a riscos ambientais o mais (iluminação inadequada, pisos escorregadios, tapetes soltos, etc). Tais riscos devem ser evitados. Os ambientes devem manter um apresentação familiar (não mudar a disposição da mobília desnecessariamente) e barras presas na parede e corrimãos devem ser instalados nos locais necessários (10).

As técnicas de fisioterapia serão as mesmas que usamos nas pessoas de terceira idade que não apresentam demência, mas a maneira de aborda-las exige habilidade especial. O paciente pode não aparecer interessado em saber como a falta de flexibilidade articular, a fraqueza muscular ou o edema poderão afeta-lo; não tem condições de entender a relação que existe. O preparo antecipado dos planos de terapêutica impede que o fisioterapeuta pareça indeciso. O preparo de explicações claras e simples darão melhores resultados. A instrução deverá ser repetida da mesma forma; o emprego das palavras diferentes poderá confundir o paciente. Não é aconselhável entrar em conversas desnecessárias, pois podem desnorteá-lo mais ainda.Lançar mãos de gestos e sinais físicos para esclarecer e reforçar as instruções exigentes (9).

São comuns as alterações de sensibilidade, por isso evitar atração, a eletroterapia e os equipamentos que exigem colaboração de participação subjetiva. O calor somente deve ser usado naqueles capazes de reconhecer e dizer quanto é demasiado quente (9).

O estabelecimento de metas realizáveis no tocante à mobilidade é muito útil. Mesmo as realizações mais modestas merecem ser recompensadas por parabéns e pelo interesse que o fisioterapeuta demonstra pela pessoa (9).

A meta de reabilitação precisa ser redefinida para assegurar que o paciente permaneça seguro, independente, e capaz de realizar atividades da vida diária e atividades instrumentais da vida pelo máximo de tempo que for razoável (8).

O processo de reabilitação pode começar enquanto o trabalho de diagnóstico está ainda sendo feito. Isso pode tornar a forma de treinamento básico em atividades da vida diária. Isso inclui o treinamento de atendentes para a assistência de paciente e a reabilitação de modificações ambientais necessárias para a segurança da pessoa confusa de modo que essa possa viver em um ambiente o mais aberto possível. Uma vez o diagnóstico tenha sido estabelecido, pode ser feito o planejamento cuidadoso para a assistência.

Nos estágios iniciais e médios da doença, a intervenção fisioterapêutica geralmente pode prolongar a habilidade de movimentar-se com facilidade (10).

É importante observar que inicialmente a intervenção fisioterapêutica pode ser potencialmente envolvida com a facilitação do planejamento motor e planejamento para compensação de perdas nas atividades de vida diária. A habilidade para andar é perdida mais tarde, e outros estudos relatam níveis comparáveis de comprometimento (7).

A intervenção fisioterapêutica para assistir o paciente e treinar os atendentes envolve a facilitação dos movimentos e planejamentos motor e o desenvolvimento ou refinamento de pistas ambientais e cognitivas para ajudar a realizar tarefas complexas (10).

O comprometimento cognitivo é o fator limitante. A análise ajuda o atendente a prover somente a ajuda que é absolutamente necessária, com os pacientes continuando a realizar sozinhos o máximo de AVDS possível; por exemplo, para escovar os dentes, o paciente precisa ser capaz de lembrar o comando, identificar a escova de dentes, e realizar a ação motora. O paciente pode somente precisar de ajuda de alguém que coloque a escova em sua mão e a guie lentamente para a boca para que seja capaz de escovar os dentes (7).

A primeira meta da reabilitação é criar um ambiente (emocional e físico) que dê suporte (trabalhar ativamente para compensar as perdas cognitivas específicas dos pacientes na medida em que forem ocorrendo gradualmente). A meta final é ajudar os pacientes a sentirem que eles são capazes, de modo que continuem a tentar fazer por si próprios as coisas que possam fazer com segurança, independentemente de permanecerem em sua casa ou estarem vivendo em uma instituição (9).

Em cada sessão os movimentos precisam ser equilibrados com períodos adequados de repouso para assegurar que o paciente não atingirá o ponto de fadiga e exaustão. São preferíveis freqüentes e breves períodos de atividade física (10).

O fisioterapeuta pode contribuir muito com a melhora da qualidade de vida do paciente e da família (7).

Objetivos da reabilitação fisioterapêutica (7,8,9):

- Diminuir a progressão e efeitos dos sintomas da doença,

- Evitar ou diminuir complicações e deformidades,

- Manter as capacidades funcionais do paciente (sistema cardiorrespiratório),

- Manter ou devolver a ADM funcional das articulações,

- Evitar contraturas e encurtamento musculares (sequelas da imobilização no leito),

- Evitar a atrofia por desuso e fraqueza muscular,

- Incentivar e promover o funcionamento motor e mobilidade,

- Orientação sobre as posturas corretas,

- Treino do padrão da marcha,

- Trabalhar os padrões do funcionamento sistema respiratório (fala, respiração, expansão e mobilidade torácica),

- Manter ou recuperar a independência funcional nas atividades de vida diária.

Consiste basicamente na fisioterapia motora, que engloba desde exercícios ativos, passivos, auto-assistidos, contra-resistência, isométricos, metabólicos, isotônicos, ou seja, qualquer tipo de movimento é bem vindo no tratamento. Quando chega a uma segunda fase esta patologia, deve-se estimular atividades para que o paciente não fique o tempo inteiro na cama, evitando assim escaras de decúbito, comumente relatadas. Alongamentos e atividades de relaxamento podem ser realizados (10).

Outras modalidades de tratamento são eficazes, como a parte de exercícios para o condicionamento aeróbico, como estimular o paciente a realizar caminhadas, tanto por percursos diferentes, ou dependendo pelo mesmo percurso, estimulando assim concomitantemente a memória do paciente. Bicicletas estacionárias também são de grande valia, assim como se possíveis trabalhos de hidroterapia (9).

Exercícios para propriocepção e equilíbrio são fundamentais para a desenvoltura do paciente, como exercícios com bastões, bola, descarga de peso gradual, andadores, percursos (10).

Pode realizar atividades em que se estimule o raciocínio do paciente, como atividades de escrever, decorar palavras, nomear objetos, que levam a um estímulo da memória (7).

Porém a principal atitude a ser tomada é a companhia que este paciente precisa, nunca deixa-lo no abandono, por isso a conversa com familiares sobre o assunto é importante, para que assim este paciente possa conviver normalmente num meio familiar, eliminando o risco de passar o resto de sua vida num asilo (6).

Conclusão

Existe uma busca de uma melhor qualidade de vida para os pacientes e dos vários tipos de tratamento para a doença de Alzheimer, com o objetivo de amenizar os sintomas. Porém enquanto não for descoberta a etiologia dessa patologia, torna-se difícil chegar á cura dessa doença.

A fisioterapia busca melhoria na qualidade de vida do paciente, sendo que o paciente com Alzheimer necessita de uma reabilitação global, envolvendo uma equipe multidisciplinar, e que a fisioterapia tem um papel fundamental tanto na reabilitação motora quanto no retorno as relações interpessoais e na obtenção de independência por parte do paciente.

Referência

1. Goldman, L.; Bennett, J.: et al. Cecil: Tratado de Medicina Interna. 2 Ed. Rio Janeiro: Guanabarra Koogan 2001.v2.

2. Harrison, T. R. Medicina Interna. 5 Ed. Rio de Janeiro: Mc Graw Hill, 2002 v2. 3. Rowland, Lewis P. et al. Merrit: Tratado de Neurologia. 9 Ed. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan, 1997.

4. Abrams, William B.; Berkow, Robert. Manual Merck de Geriatria. 1 Ed. São Paulo: Roca, 1994.

5. Papaléo Netto, Matheus. Gerontologia: A velhice e o envelhecimento em visão globalizada. São Paulo: Atheneu, 1996.

6. Serro Azul, Luis G. Carvalho Filho, Eurico T.; Décourt, Luiz. Clínica do Indivíduo Idoso. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara, 1981.

7. O´sullivan S.B., Schimitz T.J., Fisioterapia: Avaliação e Tratamentos. 3 Ed. São Paulo. Manole, 2003.

8. Umphred, Darcy Ann. Fisioterapia Neurológica. 2.ed. São Paulo: Manole, 1994.

9. Compton, Ann et al., Fisioterapia na terceira idade. São Paulo: Santos, 2002.

10. Kottke, Frederic J.; Lehmann, Justus F. Tratado de Medicina Física e Reabilitação de Krusen.. 4 Ed. São Paulo: Manole ,1994.

sexta-feira, 14 de janeiro de 2011

Avanços recentes na Reabilitação de Proteses Totais do Joelho

Following Primary Total Knee Arthroplasty

JUSTINE NAYLOR, ALISON HARMER AND RICHARD WALKER

CASE REPORT

Mrs JM, a 70 year old female, presented pre-operatively with severe tri-compartmental osteoarthritis (OA) of her right knee. On examination, she was obese (Body Mass Index (BMI) 30.8), walked with a varus thrust and a marked limp on the right, and used a walking stick. Her gait, lower limb strength, and range of motion (ROM) profiles were as follows:

Gait speed:

– Timed up-and-go (TUG) – 15 seconds.

– Timed 15-m walk – 21 seconds (0.71 m/s).

– 6-min. Walk Test (6 MWT), 322m, limited by knee pain (right > left).

Isometric strength at 90◦:

– Knee extensors: Right, 106 Newtons; Left, 150 Newtons.

– Knee flexors: Right, 58 Newtons; Left, 100 Newtons.

Knee range of motion (ROM) (passive, supine):

– Right=−10◦ to 100◦; Left=−5 ◦ to 105◦.

Symptomatically, Mrs JM reported high pain (13/20), stiffness (5.8/5), and difficulty (45.5/68) scores on the WOMAC1 subscales, and poor bodily pain (30/100) and physical function (26.6/100) scores on the SF-362 domains.

In terms of Mrs JM’s medical history, she reported bilateral knee OA (right > left) of idiopathic origin of eight year’s duration. She suffered from hypertension (which was controlled), ischaemic heart disease (IHD), and demonstrated poorly controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus (HbA1c (glycosylated haemoglobin) 8.2 %) of seven years’ duration. Consequently, her American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) anaesthetic risk score was estimated as II. Consequent to her multiple co-morbidity status, her medication usewas extensive; for her pain management in particular, a poly-pharmacy approach was evident:

1 Western Ontario & MacMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (low scores indicating better status).

2 Medical Outcome Study, Short Form-36 Health related quality of life scale (high scores indicating better

Carvedilol, 25 mg daily.

Glyceryl trinitrate, patch 25 mg daily.

Metformin, 1 g bd.

Paracetamol, prn.

Celecoxib, 200 mg daily.

Glucosamine and chondroitin sulphate.

Her haemoglobin concentration (Hb) was noted to be 139 g/l.

As part of routine anaesthetic work-up.

Socially, Mrs JM lived with her spouse in a house with 18 stairs. She had ceased recreational lawn bowls six months prior to her presentation due to pain and giving way in her right leg. She was a pensioner, reporting a low income level throughout her family life, and the highest level of education attainedwas primary (elementary) level.

INTRODUCTION

The benefits of total knee arthroplasty (TKA) for the individual with arthritis are perceived relatively quickly (usually within three to six months) and are generally pluralistic, including improvements in pain, ROM, knee stability, mobility, function, and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) (Aarons et al. 1996 A; Ethgen et al.

2004 A; Fortin et al. 2002 A; March et al. 1999 A; March et al. 2004 A; McAuley et al. 2002 A; Naylor et al. 2006a A; Pierson et al. 2003 A; Salmon et al. 2001 A; Van Essen et al. 1998 A). Consequently, TKA is estimated to be a highly cost-effective treatment option for severe arthritis (Segal et al. 2004 A). Largely ignored in costbenefit calculations, however, are the costs associated with ongoing (post-acute care)

rehabilitation. Such costs can indirectly be appreciated via the findings of March et al. (2004 A), who reported that the average number of out-patient physiotherapy visits by primary TKA patients was 10 in the first post-operative year, exceeding the average number of patient visits to any other health professional. This, of course, was in addition to any acute in-patient rehabilitation provided during the in-patient period

(an average of 12 days) and, for many (33 %), treatment in a rehabilitation facility.

We anticipate that the findings by March et al. are readily generalised as we have observed that referral to ongoing physiotherapy post-TKA is fairly routine in Australia, with out-patient based treatment predominating (Naylor et al. 2006bA). Our findings, obtained through a nationwide survey of TKA rehabilitation providers, echo earlier observations by Lingard et al. (2000A), who reported the frequent utilisation of ongoing physiotherapy post-TKA in the UK, Australia and the US, with the latter tending to rely more on in-patient services. Given that the numbers of TKA procedures have doubled in these same countries over the last decade (Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry 2004 A; Dixon et al. 2004 A; Skinner et al. 2003 A), the volumes of patients potentially requiring ongoing rehabilitation to supplement surgery must also have increased. Anecdotally, in Australia at least, there is a perception that the increased surgical throughput has not been accompanied by increases or appropriate increases in the availability of downstream (ward-based and rehabilitative) resources. This must translate at some point into a time-squeeze at the therapist-patient interface and access-block for rehabilitation services. For these reasons, the need to understand the costs and benefits of rehabilitation should be an urgent priority for health systems worldwide. Osteoarthritis (OA), the leading precipitant for TKA, is associated with significant loss of lower limb muscle strength (Fransen et al. 2003 A; Gur et al. 2002 A), walking speed (Gur et al. 2002 A; Lamb & Frost 2003 A), and function (Fransen et al. 2001 A). Exercise programmes involving patients with OA have repeatedly been shown to elicit significant yet small improvements in these parameters within relatively short time frames (for example, at two months) (see reviews by Bischoff & Roos 2003 R; Fransen et al. 2001 R). In contrast, TKA – a procedure typically reserved for recalcitrant arthritis – does not guarantee immediate improvements in these same parameters. Though significant improvements do occur early, several cross-sectional (Berth et al. 2002 A; Mizner et al. 2003 A; Walsh et al. 1998 A) and longitudinal (Benedetti et al. 2003 A; Lamb & Frost 2003 A; Lorentzen et al. 1999 A; Ouellet & Moffet 2002 A; Salmon et al. 2001 A) studies reveal shortfalls in gait, strength, and quality of life, compared to age-matched controls, several months to years after surgery. The argument for ongoing rehabilitation following TKA, therefore, is based on the following related contentions:

That age-predicted norms for muscle function, gait patterns, and physical activity levels are not spontaneously or completely achieved post-surgery, and;

That short-term exposure to prescribed interventions or physical activities will facilitate more complete recovery.

Given that the provision of acute and ongoing physiotherapeutic rehabilitation appears to be standard care across several countries, it is staggering to realise that the evidencebase which underpins rehabilitation in this area is tenuous. While there are considerable bodies of work supporting some, but not all, physiotherapeutic interventions in the acute ward phase, there is comparatively little evidence to support the various modes of ongoing rehabilitation offered either in the community or in rehabilitation wards. The trials that have been conducted (Frost et al. 2002 A; Kramer et al. 2003 A; Moffet et al. 2004; Rajan et al. 2004 A) all compared one mode of ongoing physiotherapy to another and did not include a true non-interventional control. Thus, the contribution of rehabilitation per se to the overall recovery process is uncertain.The lack of definitive evidence is problematic for policy makers worldwide, as health service providers are increasingly required to justify the high costs of health care, while the demand for services (in this case, rehabilitation) is increasing through sheer volume alone. Furthermore, the lack of evidence is problematic at the coalface, given that variation in practice is likely to be (Roos 2003C), and has been observed to be (Naylor et al. 2006b A), the rule, further undermining our capacity to identify best practice.

This chapter addresses questions concerning the efficacy of various acute physiotherapeutic interventions and longer-term rehabilitative strategies Mrs JM may be exposed to through her journey of recovery. Questions concerning the impact of prosthesis type or specific surgical choices on the potential to rehabilitate or the mode of rehabilitation required are also briefly addressed. Mrs JM presents fairly typically for an elderly patient awaiting TKA for severe knee OA (Ackerman et al. 2005 A; Bozic et al. 2005 A; Heck et al. 1998 A; March et al. 2004 A; Mizner et al. 2003 A; Naylor et al. 2006a A; Ouellet & Moffet 2002 A). Notably, the measured variables are frequently utilised and recommended for the evaluation of OA and TKA (Bellamy et al. 1988 A; Ethgen et al. 2004 R; Fransen et al. 2003 A; Kennedy et al. 2005 A; March et al. 1999 A; March et al. 2004 A; Ouellet & Moffet 2002 A; Petterson et al. 2003 A). Compared to norm data or age-matched controls (see Table 1),

Table 1. Normative or age-matched physical and health-related quality of life data

Australian Age-Matched

Norm Data Control Data

Physical Function

SF-36 Physical Function 65.2 1 —

WOMAC Physical Function NA —

Walking Speeds

Timed up-and-go (sec) — 8–11 2,3,4

15-m walk (m/sec) — 1.33–1.84 2,5

6-minute walk (m) — 448 2

Isometric Muscle Strength

Knee Extensors (N) — 225 (sd 49)6

Knee Flexors (N) — 139 (36)6

Health-Related Quality of life

SF-36 General Health 64.1 —

SF-36 Vitality 60 —

SF-36 Mental Health 75.3 —

Knee Range of Motion

Total — 143◦4

Pain Scores

SF-36 Bodily Pain 69 —

WOMAC Pain NA —

Legend: 1National Health Survey SF-36 Population Norms, ABS 1995 (unstandardised mean scores, female); 2Steffen et al. 2002 A; 3Ouellet & Moffet 2002 A; 4Shumway-Cook et al. 2000 A; 5Walsh et al. 1998 A; 6Fransen et al. 2003A; NA=not available at time of publication (Australian data). Normative data from large population sets are provided where available; otherwise, age-matched data, sourced from relevant osteoarthritis or knee replacement trials, are cited.

The reported daily consumption of analgesic and anti-inflammatory medications is consistent with the high pain scores, and the use of a walking aid is somewhat typical for degenerative joint disease. It is important to note that our own experiences indicate the analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and walking aid profiles are not, in isolation, reliableindicators of severity or improvement, as behavioural factors greatly influence their use.

The patient’s co-morbidity profile is also typical for this patient population, with hypertension in particular being the most common co-morbidity observed in several TKA cohorts (Denis et al. 2006 A; Moffet et al. 2004 A; Naylor et al. 2005 A). Additionally, some physiological limitation is qualitatively suggested by the ASA score, again not atypical of TKA recipients (Bozic et al. 2005A; Naylor et al. 2005aA; Pearson et al. 2000 A). Given the self-exertion nature of many rehabilitation interventions, recognising the physiological limitations imposed by concurrent illnesses is an essential consideration in any rehabilitation programme. Likewise, the socioeconomic factors, highlighted as low income and education levels, are associated with poorer pre-operative function (Ackerman et al. 2005 A) and some post-surgical outcomes (Fortin et al. 1999 A). For the therapist, these factors become relevant when setting realistic long-term patient goals and when benchmarking rehabilitation outcomes between surgical units.

REHABILITATION IN THE ACUTE PHASE

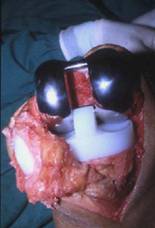

OPERATIVE HISTORY AND ACUTE POST-OPERATIVE

PRESENTATION

Relevant operative details:

General anaesthetic + femoral and sciatic nerve blocks.

Tri-compartmental primary TKA.

Cemented femoral, tibial, and patella components.

Fixed-bearing, increased congruency, polyethylene bearing.

Posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) sacrificed.

Release of medial collateral ligament.

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) removed.

Intra-articular low suction wound drain in situ.

Presentation 18 hrs post-op (Day 1):

Symptoms:

– Reporting 2/10 pain on visual analogue scale, using patient-controlled analgesia c/o numbness and lack of movement in foot.

Mobility:

– In bed, awaiting assessment by physiotherapist.

ROM:

– Start flexion, –10◦.

– End flexion, 60◦.

– Restricted by oedema and crepe bandaging.

– Quadriceps lag, 15◦.

Vital observations:

– BP 110/70 (normally 130/80).

– HR 95–100.

– RR 18.

– SpO2 97 % (3 L/min. O2, nasal prongs).

Blood results:

– Hb 105 g/l.

– Blood glucose level (BGL) 7.7 mmol·l−1.

Other medication:

– Anti-hypertensives and metformin withheld.

– Twice daily protaphane, with top up sliding scale to maintain blood glucose control.3

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Rehabilitation in the acute phase is largely directed towards the minimisation of the effects of surgical trauma and rendering the patient safe for discharge. The rehabilitative strategies include the use of modalities and techniques to reduce intra- and extra-articular oedema, improve or maintain knee ROM, offset the adverse effects of bed rest, and assist independent ambulation. With respect to the determination of discharge readiness, it is recognised that some surgical units specify a minimum flexion ROM before a patient is deemed fit (Ganz & Benick 2004 Abstract), while others rely more on the level of function achieved (Munin et al. 1998 A; Naylor et al. 2006b A). Though speculative, the latter approach may have evolved secondary to an ever-present need to maintain patient flow in order to keep wait lists in check. In this context, the need to achieve specific physical milestones, such as a minimum flexion requirement, becomes less urgent (Benick et al. 2004 Abstract). It is also recognised that the threshold for discharging patients to an in-patient rehabilitation unit may differ between surgical units, with a lower threshold likely in the private market.

The nature and timing of acute care rehabilitation has also been altered over the last 10 years via the introduction of specific multi-disciplinary care pathways (protocols). Such pathways have procured impressive (up to 50 %) decreases in acute length of stay (LOS) (Brunenberg et al. 2005 A; Dowsey et al. 1998 A; Munin et al. 1998 A; Pearson et al. 2000 A;Wang et al. 1997 A), which must inevitably impact on the goals of rehabilitation, as the therapist-patient interface has contracted considerably at ward level. Finally, central to effective rehabilitation both now and in the longer-term, is good pain management. It is beyond the scope of this chapter to review the evolution of pain management in this context, however; suffice it to say that physiotherapists act as barometers of good pain control in their estimation of whether a patient can engage in their rehabilitation effectively.

3 Additionally, referral to an endocrinologist was initiated on admission, and the recommendation was to add 1/2 80 mg tab of gliclazide twice daily once metformin is recommenced, with the option to increase to 80 mg twice daily if needed (i.e. if HbA1c remains high).

Arthroplasty, knee, Cryotherapy.

Arthroplasty, knee, CPM.

Arthroplasty, knee, walking aid progression.

Arthroplasty, knee, exercises.

Studies were considered appropriate if the subjects had undergone primary TKA, were randomised to receive the treatment(s) under investigation, and the treatment(s) was (were) conducted in the acute in-hospital phase. In cases where a systematic review existed for a given intervention, this predominantly formed the basis for the review, to avoid duplication. Studies focusing on multi-disciplinary and multi-faceted clinical pathways were generally not included. Only studies written in English were reviewed. This review does not include the effects of pre-operative programmes on outcomes. For these, the following reviews are recommended: Ackerman et al. 2004 R; McDonald et al. 2004 R.

QUESTION 1

Does cryotherapy work?

External cooling of the knee surfaces has been shown, in the absence of haemarthrosis, to lower intra-articular temperatures in humans by 2.7–5 ◦C (Martin et al. 2002A).

This, together with the local effects of cold therapy on neural and vascular function, presumably motivates the use of cryotherapy post-TKA for the purposes of reducing pain and swelling. The use of cryotherapy has been observed to be inconsistent in the acute phase following TKA, in terms of both the factors governing its application (Barry et al. 2003) and whether it is utilised at all (Naylor et al. 2005 A, 2006b A).

To date, cryotherapy post-TKA has not been systematically reviewed, but several RCTs have been conducted (Gibbons et al. 2001 A; Healy et al. 1994 A; Ivey et al. 1994 A; Scarcella & Cohn 1995 A; Smith et al. 2002 A; Webb et al. 1998 A). Only one study (Webb et al. 1998 A), comparing cold compression to a non-interventional control, observed significantly less blood transfusions, analgesic consumption, and pain with cold therapy. Of course, the contribution made by the compression component could not be differentiated in this study. Of note, despite the pain relief and blood loss benefits, no differences in ROM acutely or at 12 weeks were observed.

For the majority of the remaining studies in this area, no or minor differences have been observed between those receiving and not receiving early cryotherapy on several outcomes, including LOS, transfusion needs, swelling, ROM, pain, and analgesic use.

Having said this, the interpretation of the impact of cryotherapy in these studies is clouded by comparisons with alternative treatments (such as compression bandaging or alternative cold therapy) (Gibbons et al. 2001 A; Healy et al. 1994 A; Smith et al.2002 A) rather than comparisons with true non-interventional controls Healy and colleagues (1994 A) compared cryotherapy to ice packs. Smith et al. (2002 A) used cold therapy in both groups after 24 hours. Scarcella and Cohn (1995 A), with their sample of 24 TKA patients, were not likely to have had sufficient power to detect differences between their groups when others (Smith et al. 2002 A) have required a sample of 80 for the same outcome variables. Finally, Gibbons et al. (2001 A) did not account for possible gender differences in Hb levels between the treatment and control groups, which themselves differed in their gender profile. This may have explained why cold compression was not associated with a lower transfusion requirement in this study despite being associated with smaller post-operative blood losses. Even with the lack of irrefutable evidence demonstrating that there is no additional benefit from cryotherapy, various authors (Healy et al. 1994 A; Smith et al. 2002 A) have concluded that its costs outweigh its benefits and that compression is preferred in light of this.We conclude that although at this stage it would appear that cryotherapy offers no additional benefits beyond those which could be achieved with compression alone, the methodological limitations of the majority of studies conducted render this issue unresolved.

Regarding Mrs JM, the available evidence does not strongly support or refute the use of cryotherapy, nor is it clear whether compression bandaging alone is superior to it. Thus, the therapist would be justified in trying either. Ideally these modalities would be applied both before and after physiotherapy; at the very least, pain, oedema and ROM should be monitored pre- and post-application. However, Mrs JM’s initial numbness – presumed at this stage to be a hangover from her intra-operative regional anaesthetic – may delay the commencement of ice therapy. Of course, neural deficits beyond 24 hours will need to be differentiated from possible chronic loss due to diabetic neuropathy. Though speculative at this point, the presence of the haemarthrosis following TKA may undermine the impact of external ice applications, rendering the effects of compression bandaging more important.

QUESTION 2

Does continuous passive motion work?

Continuous passive motion (CPM), like cryotherapy, is an adjunctive rehabilitation tool intended to decrease swelling and haemarthrosis, and enhance soft tissue healing and joint ROM (Milne et al. 2003 A). In contrast to cryotherapy, however, CPM has been subject to many RCTS involving TKA recipients (n=59), one Cochrane review (Milne et al. 2003 A), and one qualitative review (Lachiewicz 2000 R). Thus, more definitive conclusions can be drawn regarding its effectiveness.

Milne et al. (2003 A), based on a meta-analysis, concluded that CPM combined with standard physiotherapy was associated with a small increase in flexion ROM at two weeks (4.3◦ weighted mean difference (WMD4)), decreased LOS (0.69 days WMD),and a decreased risk of manipulation within the first month (relative risk 0.12).

4 WMD: difference between control and treatment group is weighted by the inverse of the variantion.

CPM was not found to improve passive ROM. The authors did conclude, however, that information and protocol biases were present in the review due to inadequate reporting of some variables (for example, whether ROM was passive or active) and inconsistent protocols (for example, pain relief and pre-operative education) across studies. Information on ideal dose and application could not be derived. In light of these facts, the authors recommended that the potential benefits of CPM be weighed against the possible increased costs and inconvenience, and that more research be conducted to determine the optimum treatment parameters. Not included in the analyses were the effects of CPM on midline wound healing, bleeding overall, and hospital costs. These have been shown to be a concern in some trials (Lachiewicz 2000 R).

Since the publication of the meta-analysis by Milne and colleagues, only one other RCT has been conducted in TKA patients. Denis et al. (2006 A) did not observe any differences in discharge (∼ eight days post) ROM, LOS,WOMAC function, and TUG times between those treated with conventional physiotherapy plus 35 or 120 minutes of CPM daily, and those receiving conventional physiotherapy only.With the exception of LOS, these results confirm the conclusions of the aforementioned metaanalysis.

It is unfortunate, however, that the number of manipulations post-discharge was not monitored given that this is perhaps the most clinically relevant outcome concerning CPM. In terms of current clinical practice, we observed that CPM does not appear to be in routine use in Australia (Naylor et al. 2006b A). Whether this is the case elsewhere is unknown as there are no other survey data concerning this. We also observed in our unit, where CPM was routinely prescribed, that only 40 % of patients received it (Naylor et al. 2005 A). Protocol deviance was explained by a combination of lack of awareness of the protocol by rotating physiotherapists, and their perceived lack of need – the latter possibly explained by the fact that functionality and not ROM primarily determines discharge at our unit. At this point in time, our CPM practices, together with our pain relief and pre-operative education policies, are under review, as the number of manipulations performed within six months of surgery has increased in recent times.

Regarding Mrs JM, in view of the risk of manipulation alone, CPM should be initiated at least once per day for several hours during bed rest periods. This recommendation ideally applies to units where CPM is readily available and where medical and nursing staff can apply it. Though speculative, CPM may be of particular benefit to Mrs JM given her poorly controlled diabetes (evidenced by the elevated HbA1c of 8.2 %; non-diabetic range 3–6 %). Glycosylation (permanent protein modification by glucose) of collagen or elastin as a result of persistently high BGL may result in tissue stiffness (Paul & Bailey 1996 B), hence Mrs JM may be at a greater risk of manipulation.5

5 22%of patients presenting for manipulation under anaesthesia for frozen shoulders had diabetes (Hamdan

& Al-Essa 2003).

QUESTION 3

What is the evidence for exercise and early ambulation to improve ROM, decrease length of stay, and prevent deep venous thrombosis?

Only one study has compared the outcomes of patients who received formal knee flexion exercises in addition to standardised physiotherapy with those who received standardised physiotherapy only (Ganz & Ranawat 2004 Abstract). Though formal knee flexion exercises were associated with greater active knee flexion at one week, this did not translate into any functional differences (such as stair ambulation or use of aids) or shorter LOS. At three and 12 months, there were no differences in active knee flexion. No studies were found focusing on active knee extension. Despite the lack of evidence in support of specific active exercises, we have observed the prescription of lower limb exercises in the acute stage to be routine in Australia (Naylor et al. 2006b A). This notwithstanding, as there does not appear to be any routine case to suggest active exercises are detrimental in this patient group, we find no reason for not including them in the therapy repertoire.

Similarly to active exercises, the arguments for early ambulation post-TKA rest largely on the desire to minimise the well-known adverse effects of bed rest and to accelerate discharge from hospital. To our knowledge, only one RCT has been conducted (Munin et al. 1998 A) which highlights the specific benefits of early rehabilitation, including early ambulation (commencing Day Three versus Day Seven), on LOS, functional performance, and Deep Vein Thrombosis rate. Though the specific contribution attributable to early ambulation alone cannot be reliably estimated, the absence of evidence to the contrary suggests protocols aimed at early ambulation are desirable. We do qualify this statement, however, in that we recommend an assessment of the patient’s medical stability (including blood pressure, heart rate and rhythm, BGL, oxygen saturation levels, and Hb) precedes any physiotherapy intervention.

Regarding Mrs JM, her lower limb neural deficit will preclude ambulation and some bed exercises until it resolves. A combination of closed- and open-chain isometric, concentric, and eccentric exercises will be prescribed for the flexor and extensor muscle groups in her lower limbs. Ambulation will commence after removal of the wound drains. Her cardiovascular history necessitates close monitoring of her vital signs prior to her participating in any exercise, however. Her low Hb is typical at this stage, given the acute blood losses (mean 608 mls) associated with the surgery (Naylor et al. 2005 A), and, at her current level, does not warrant a transfusion (NH&MRC & ASBT 2001 A).

QUESTION 4

What evidence guides walking aid progression?

The literature search yielded no RCTs investigating the optimal rate of walking aid progression. We are aware of surgical units that dictate the rate of progression according to the presence or absence of cement. In our unit, all patients are progressed and discharged on crutches, with instructions to weight-bear as tolerated unless otherwise indicated. It is not clear at this stage whether the rate of progression onto a walking stick or to complete independence from walking aids is a concern for longterm prosthesis stability, the restoration of normal gait patterns, or the evolution of back pain.

QUESTION 5

Does electrical stimulation work?

The electrical stimulation of the knee extensor muscles post-TKA is based on the premise that voluntary activation is not sufficient to restore strength (Avramidis et al. 2003A). Three studies were identified that randomised the use of electrical stimulation to the vastus medialis or quadriceps femoris during CPM, commencing in the acute period and given alongside a standardised physiotherapy programme. Gotlin et al. (1994 A) and Haug and Wood (1988 A) observed that patients receiving two to three hours of muscle stimulation daily until discharge experienced less extensor lag and shorter LOS. In a longer-term study, Avramidis et al. (2003 A) observed that patients receiving electrical stimulation for two hours twice daily from the second post-operative day for six weeks, attained a faster walking speed at six weeks, and this effect carried over until the 12th week. The authors concluded that the greater walk speed was a consequence of more rapid quadriceps recovery and, as such, a greater ability to participate in exercise. It should be noted that the control group did not receive any standardised physiotherapy post-discharge. The addition of a third group that received standardised physiotherapy for six weeks would have helped to clarify whether electrical stimulation was superior to or simply a replacement for voluntary muscle activation. While the use of electrical stimulation looks promising, the technical and potentially cumbersome nature of the procedure, and the prerequisite for effective communication between patient and therapist for safety reasons, may have deterred widespread adoption of this treatment option.

Regarding Mrs JM, assuming availability of the device and competency of both the staff and patient in its use, intermittent neuromuscular stimulation is an appropriate rehabilitation intervention, given her quadriceps lag.

QUESTION 6

What is the evidence for hydrotherapy?

No RCTs were identified concerning the efficacy of hydrotherapy post-TKA. We recognise that it is a treatment option where facilities exist (Naylor et al. 2006b A) and that a non-randomised trial has been conducted in Germany (Erler et al. 2001 A).

No recommendations can be made at this stage, but note that, at the very least, the integrity of thewound is paramount for hydrotherapy to be considered a viable option. REHABILITATION IN THE POST-DISCHARGE PHASE

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

The post-discharge phase of rehabilitation commences after discharge from an acute care facility. Goals of rehabilitation in the earlier post-discharge phase focus upon increasing the level of independence of the patient, which may include weaning off a walking aid, maintaining and improving knee joint ROM, controlling or reducing residual oedema, increasing muscle strength and endurance, and gradual return to work and leisure activities. In the later phase of post-discharge rehabilitation, goals include further improvement of muscle strength and endurance, improvement of cardiovascular fitness, and full return to work and leisure activities.

The sources of evidence reviewed for specific rehabilitative interventions in the post-acute phase consisted of RCTs and systematic reviews. In order to identify the relevant literature, the following combinations of terms were used in an electronic literature search of MEDLINE, CINAHL and EMBASE:

Total knee replacement, with subject headings: arthroplasty, replacement, knee; knee prosthesis; TKR. Rehabilitation, with all subject headings. Physiotherapy, with subject headings: exercise therapy; orthopedics; physical therapy (specialty); physiotherapy. The initial literature search yielded 230 studies. For the present review, studies were only included if the subjects had undergone primary TKA, were randomised to receive the treatment(s) under investigation, and the treatment(s) was (were) conducted in the post-acute phase. Only studies written in English were reviewed. Only five trials satisfied these criteria, thus revealing the paucity of evidence for effects of rehabilitation in the post-acute phase. One study (Mitchell et al. 2005 A) included pre-operative physiotherapy in one group and was thus excluded. The remaining four trials differed markedly in their methodology and investigated the effects of out-patient physiotherapy versus home-based rehabilitation (Kramer et al. 2003 A; Rajan et al. 2004 A); traditional versus functional home-based exercise (Frost et al. 2002 A); and intensive versus usual care treatment (Moffet et al. 2004 A). Due to the limited number of studies identified and the holistic nature of the physiotherapy programmes described, it was not possible to examine the effect of a single treatment component in the postacute phase. In addition to the five reports of randomised trials, one recent review that presented current evidence from experts on knee and hip arthroplasty was identified (Jones et al. 2005 R).

QUESTION 7

What is the evidence supporting early post-discharge rehabilitation?

Three RCTs have examined the effects of physiotherapy provided in the early postdischarge phase of rehabilitation; that is, commencing immediately after discharge from acute care. Kramer et al. (2003 A) investigated effects of clinic- versus homebased rehabilitation. All patients were provided with advice on knee management and were prescribed home strengthening and ROMexercises, the basic form of which they were taught during the acute in-patient period. The home-based group received weekly phone calls from a physiotherapist, whereas patients in the clinic-based group attended the clinic once or twice weekly until three months post-operation. At three and 12 months post-operation there was no difference between groups on any outcome measures, which included WOMAC total and pain and function subscales, SF-36 total, knee flexion range, 30-second stair test, and 6MWT. Similarly, another study (Rajan et al. 2004 A) found no additional benefit of out-patient physiotherapy compared with a home exercise programme at three, six, or 12 months; however, there was no description of the physiotherapy interventions, and the only outcome measure reported was knee flexion range. Provided that sufficient knee range is available for performance of ADL, this outcome measure is a poor sole criterion upon which to judge treatment efficacy in the post-acute phase. Frost et al. (2002 A) compared two home-based programmes – usual care (for example, ROM exercises, quadriceps, and hamstrings strengthening) versus functional exercises (rising from a chair, lifting the leg onto a step, and walking) – that commenced immediately after hospital discharge. At the one-year follow-up assessment there was no difference between groups in 10 m walking speed, pain, knee flexion range, or leg extensor power.

All three of the above studies used intention-to-treat analysis; one study employed therapist blinding (Frost et al. 2002A) and another, partial blinding (Kramer et al. 2003 A), and subjects were randomly allocated to groups. Losses to follow-up were 3 % (Rajan et al. 2004A), 23%(Kramer et al. 2003A), and 43%(Frost et al. 2002A), and all studies described reasons for drop-out. Very few adverse events occurred using the exercises prescribed in these studies. According to the principles of evidence-based practice (Herbert et al. 2005 A/R), the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) assigned the following scores to each of the studies: Frost et al. 6/10; Kramer et al. 6/10; and Rajan et al. 7/10; indicating that these studies all provide a moderate level of evidence. It can be concluded that patient outcomes one year post-TKA are not affected by location of rehabilitation delivery (out-patient physiotherapy clinic versus home) or type of exercise (usual versus functional). However, loss to follow-up may be affected by the level of supervision provided by the physiotherapist (out-patient attendance or phone call monitoring versus no monitoring). Larger trials, which provide a greater power to detect small differences in outcome measures, may necessitate revision of these conclusions. Patient outcomes at one year post-TKA indicate that although significant improvements were evident compared to before surgery, there is still a residual level of pain, disability, and loss of knee flexion range; and that patients only just attain the lower limits of age-matched normal function, for example walking speed. A lack of sufficient exercise intensity during rehabilitation may partly contribute to these shortfalls in recovery, but it was not possible to calculate exercise dosage from these trials since exercise intensity was largely patient determined or else it was not described.

QUESTION 8

What is the evidence supporting later post-discharge rehabilitation?

One RCT only (Moffet et al. 2004 A) has examined the effect of commencing rehabilitation later in the post-discharge phase. Ability to exercise in this stage would be anticipated to be greater than in the early post-acute phase, when anaemia, pain, oedema, and residual effects of anaesthesia can cause significant limitation. Moffet et al. (2004 A) employed intention-to-treat analysis: blinding of evaluators; random allocation of subjects; and had only ∼10 % loss to follow-up, with all drop-outs being described, thus providing a moderate to strong level of evidence (PEDro score 7/10). Two months after TKA, patients were randomised to either usual care (strength training, ROM exercise, ice, gait retraining; 26 % also received home visits) or to an intensive 12-week supervised physiotherapy programme, which also included the usual care components. Intensive sessions included strength (for example, maximal isometric contractions of quadriceps and hamstrings; functional exercises such as sit-to-stand and stairs) and endurance exercise training (walking or cycling at 60– 80 % of maximum predicted heart rate for up to 20 min.). Exercise intensity was progressed as required, however, while number of repetitions was reported, intensity of strength training was difficult to assess from the data provided. No adverse events from treatment occurred. At six months post-TKA, patients in the intensive exercise group had increased their 6MWT by 31 % (93 m), compared to 25 % (72 m) increase in the usual care group; a significant effect size between interventions of ∼9 %. Significant treatment effect differences of a similar magnitude were evident in the WOMAC subscales of pain, stiffness, and difficulty in performing ADL. One year after TKA, patients in the intensive group tended to have a higher 6 min. Walk Test distance (P = 0.06; 400 m or ∼1.1 m·s−1, which placed them at the lower limit of normal for their age) than the control group (370 m; 1.03 m·s−1), and both groups had similar levels of pain, stiffness, and difficulty performing tasks. This study demonstrates that more intensive rehabilitation, commenced in the later post-acute phase, results in greater improvements in walking speed at six months post-TKA (and probably also at 12 months, given the near statistical significance and relatively low subject number). Therefore, usual care physiotherapy after TKA probably provides less than optimal stimuli, and patients could likely make further significant gains if sufficiently challenged in the post-discharge rehabilitation period. Further, the authors suggest that increasing the exercise intensity and prolonging the programme may yield greater treatment effects. If so, this not only has important functional relevance for the patient, but also has implications for the progression or retardation of common co-morbidities such as hypertension and type 2 diabetes.

POST-DISCHARGE REHABILITATION FOR MRS JM