Alzheimer disease (AD) is an acquired disorder of cognitive and behavioral impairment that markedly interferes with social and occupational functioning. It is an incurable disease with a long and progressive course. In AD, plaques develop in the hippocampus, a structure deep in the brain that helps to encode memories, and in other areas of the cerebral cortex that are used in thinking and making decisions. Whether plaques themselves cause AD or whether they are a by-product of the AD process is still unknown.

Essential update: Memory tests plus brain imaging help detect early, asymptomatic AD

A study of 129 cognitively normal adults aged 65-87 years (mean, 73.7 years), presented at the Alzheimer's Association International Conference (AAIC) 2013, indicated that a combination of memory tests and brain imaging may help identify the earliest stages of AD before symptoms appear.

[1] In this study, poor episodic memory in the context of synaptic dysfunction and elevated amyloid identified subjects who were at high risk for progression to AD dementia.

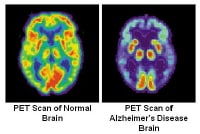

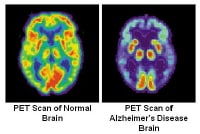

Study subjects underwent testing of memory and executive function along with fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) and amyloid deposition with C 11 Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB PET).

[1] The researchers found that amyloid burden and synaptic dysfunction independently predicted episodic memory performance. Subjects with worse memory performance had higher PiB deposition and lower FDG metabolism in regions of the brain commonly affected in AD.

Some individuals had worse memory scores and lower FDG metabolism (synaptic dysfunction) but a normal PiB scan (no amyloid deposition), which indicated that not all memory changes were a result of amyloid plaques.

[1] Individuals who performed worse on nonmemory executive function tests also had lower FDG metabolism but a normal PiB scan. More highly educated individuals had normal performance on memory tests despite lower FDG metabolism and higher PiB retention.

Signs and symptoms

Preclinical Alzheimer disease

A patient with preclinical AD may appear completely normal on physical examination and mental status testing. Specific regions of the brain (eg, entorhinal cortex, hippocampus) probably begin to be affected 10-20 years before any visible symptoms appear.

Mild Alzheimer disease

Signs of mild AD can include the following:

Memory loss

Confusion about the location of familiar places

Taking longer to accomplish normal, daily tasks

Trouble handling money and paying bills

Compromised judgment, often leading to bad decisions

Loss of spontaneity and sense of initiative

Mood and personality changes; increased anxiety

Moderate Alzheimer disease

The symptoms of this stage can include the following:

Increasing memory loss and confusion

Shortened attention span

Problems recognizing friends and family members

Difficulty with language; problems with reading, writing, working with numbers

Difficulty organizing thoughts and thinking logically

Inability to learn new things or to cope with new or unexpected situations

Restlessness, agitation, anxiety, tearfulness, wandering, especially in the late afternoon or at night

Repetitive statements or movement; occasional muscle twitches

Hallucinations, delusions, suspiciousness or paranoia, irritability

Loss of impulse control: Shown through behavior such as undressing at inappropriate times or places or vulgar language

Perceptual-motor problems: Such as trouble getting out of a chair or setting the table

Severe Alzheimer disease

Patients with severe AD cannot recognize family or loved ones and cannot communicate in any way. They are completely dependent on others for care, and all sense of self seems to vanish.

Other symptoms of severe AD can include the following:

Weight loss

Seizures, skin infections, difficulty swallowing

Groaning, moaning, or grunting

Increased sleeping

Lack of bladder and bowel control

In end-stage AD, patients may be in bed much or all of the time. Death is often the result of other illnesses, frequently aspiration pneumonia.

See

Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Means of diagnosing AD include the following:

Clinical examination: The clinical diagnosis of AD is usually made during the mild stage of the disease, using the above-listed signs

Lumbar puncture: levels of tau and phosphorylated tau in the cerebrospinal fluid are often elevated in AD, whereas amyloid levels are usually low; at present, however, routine measurement of CSF tau and amyloid is not recommended except in research settings

Imaging studies: Imaging studies are particularly important for ruling out potentially treatable causes of progressive cognitive decline, such as chronic subdural hematoma or normal-pressure hydrocephalus

[2]

See

Clinical Presentation and

Workup for more detail.

Management

All drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of AD are symptomatic therapies that modulate neurotransmitters, either acetylcholine or glutamate. The standard medical treatment for AD includes cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs) and a partial N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) antagonist.

[3, 4]

The following classes of psychotropic medications have been used to treat the secondary symptoms of AD, such as depression, agitation, aggression, hallucinations, delusions, and sleep disorders

[5] :

Prevention

There are no proven modalities for preventing AD,

[3] but evidence, largely epidemiologic, suggests that healthy lifestyles can reduce the risk of developing the disease; the following may be protective

[6, 7] :

Physical activity

Exercise

Cardiorespiratory fitness

Diet: Although no definitive dietary recommendations can be made, in general, nutritional patterns that appear beneficial for AD prevention fit the Mediterranean diet

See

Treatment and

Medication for more detail.

Image library